- Your Commonbase Weekly

- Posts

- I Was Wrong About Mobile

I Was Wrong About Mobile

A library engaged with real life is more vibrant than one of shelves

Synthesize [Mini Essay]

I was under the distinct impression that Your Commonbase was meant to be a desktop application.

I thought that the desktop computer was the best framing for a personal library. In fact the personal in Personal Library Science is derived from Personal Computers, the garage-bound machines of the hobbyist desktop era of the 1970s and 1980s.

I had assumed that given the nature and function of a personal library, the flexibility that computers provide would allow for a more organic user experience. Mobile phones exist in extremely rigid constraints, they suffer from maximal packaging and minimal compute (where’s my terminals? where’s my sysutils? where’s big chungus?). It’s one thing to be connected to the Internet, it’s a whole other thing to be connected to a list of apps.

But ever the indecisive, I gave myself a back door (a more generous interpretation is that I was being pragmatic).

I decided to build a web application. That way, I’d have the ability to “have a mobile presence” while prioritizing desktop.

While I believe I largely succeeded in the vision I had for the web app, as I added more features I began to notice a few worrying trends:

The features of the web app were becoming more and more “mobile” in nature as the updates came in

In a world of phones, the computer is only used for work

I was shocked by #1. Many of the most effective UX experiences on the web app involved mobile “tricks”, like swiping, panning, zooming etc. Why is this the case I wondered, why are these gutters on the sides so large, why are the keyboard shortcuts mapped to swiping behaviors? Am I just a millennial trapped in 2007 in a 2025 body? Or is the touch screen a better mode of computation? I wouldn’t dare to dive further, lest I dislike what answers I dredge up.

#2, on the other hand, was less of a surprise. As a New Yorker, the world was beckoning, while my library was stuck at home. The New York public transit network is a vast web of delays and transfers, and the only guarantee is that everyone will be looking at their phone.

This city is filled with Easter eggs, and our society has decided it is critical to build thin-form-factor-technologies-with-ever-increasing-lens-sizes to capture these at a moment’s notice. The computer is for power use, and a person is only “in power” a few hours of the day, tops (I’m writing this on a computer, fwiw, and I fully plan on scrolling my phone in bed later).

So I broke. I built a mobile app.

And fuck…it’s awesome.

I’ll highlight four features that I think make the mobile app for YCB a league of it’s own from the web app.

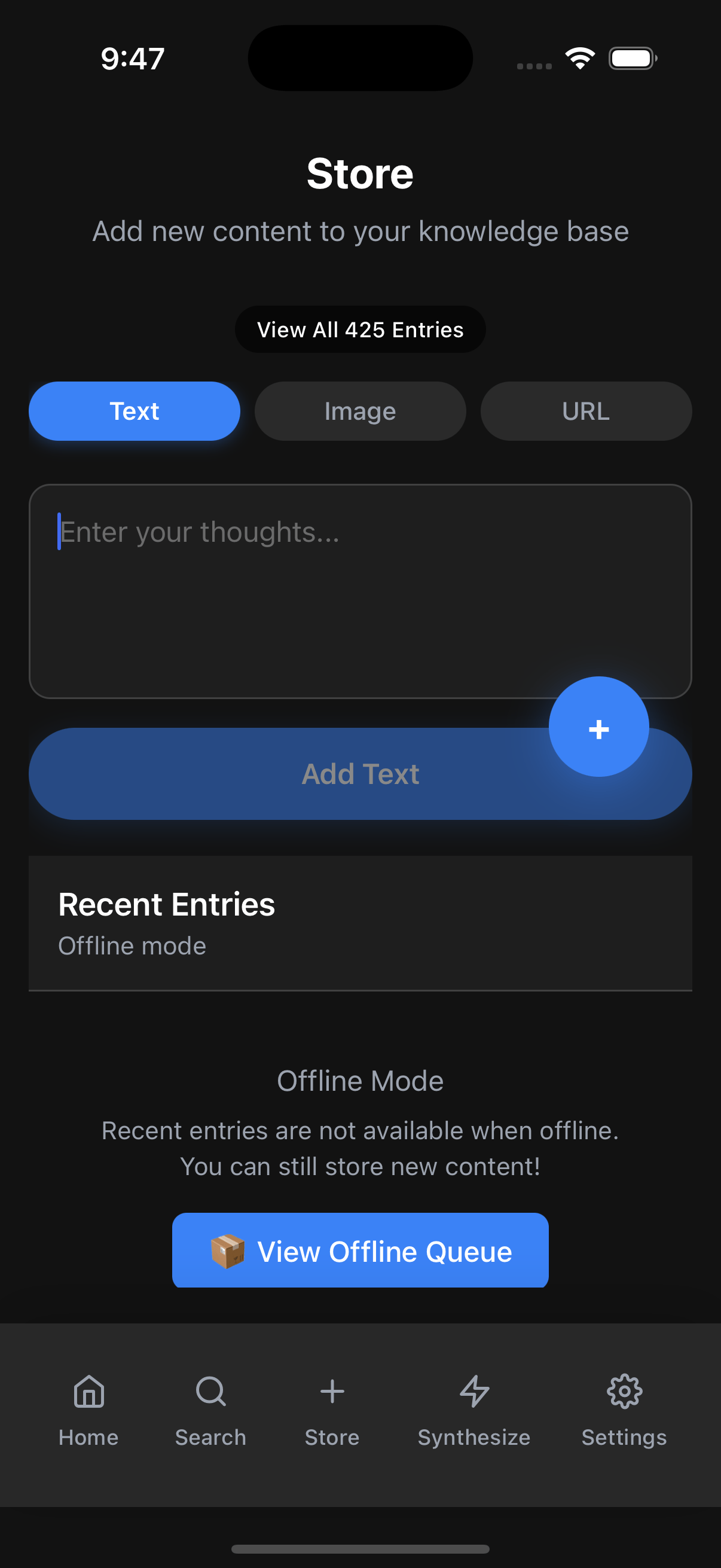

1. Offline Queue

This is the initial reason I wanted the mobile app to exist. Being able to save thoughts and images in particular and process them later, in a era with less than stable cell connection, was a priority to me.

I tried to make it on the web app, I tried to leverage local storage, cookies, what have you.

But a SQLite implementation on a mobile device is just…better.

inspired by spotify offline mode, routes user to store page

you can store text and images offline, no problem!!

the queue will auto process when it detects it is back online

The Share Sheet feels so good. It’s the closest to an in context app experience YCB can provide. I added the ability to do computational work (in this case, automatically running a semantic search) on entries saved while out and about. It’s a great way to “window shop” YCB.

Your Commonbase Sharing is Caring!

optional titles do a lot of work, it turns out

this is the real juice. immediate neighbor feedback from the share sheet?? chefs kiss

Lock screen and home screen widgets too!

3. A Healthy Feed

Let's not kid ourselves here. We're not using our phone to solve cancer or work on nuclear fusion physics problems. Most of the time that we're on our phone, we're scrolling feeds. So wouldn't it be better to scroll a feed of stuff that isn't just emotionally incisive? The stuff that you put in and that you're proud of?

(NB: The way people talk about their phones is substantially different than the way that they talk about their computers.

People often say that they need to escape from their phone, that they need to put distance between it and them.The way people talk about their phones is like this limiting object that they feel forced to look at for a number of hours a day.

But I don't generally hear that about computers outside of the people who spend hours a day on the computers and are "extremely online." But many of the people who are extremely online are just online on their phones anyway.

Whereas when people talk about their desktop computer they are doing something creative, perhaps like programming, making music, or making art — or perhaps answering emails or Slacks, even though that’s become a phone task as well as of late. I don't know what this says about the form factor of the phone vs the form factor of the desktop computer, but I think it's pretty interesting.)

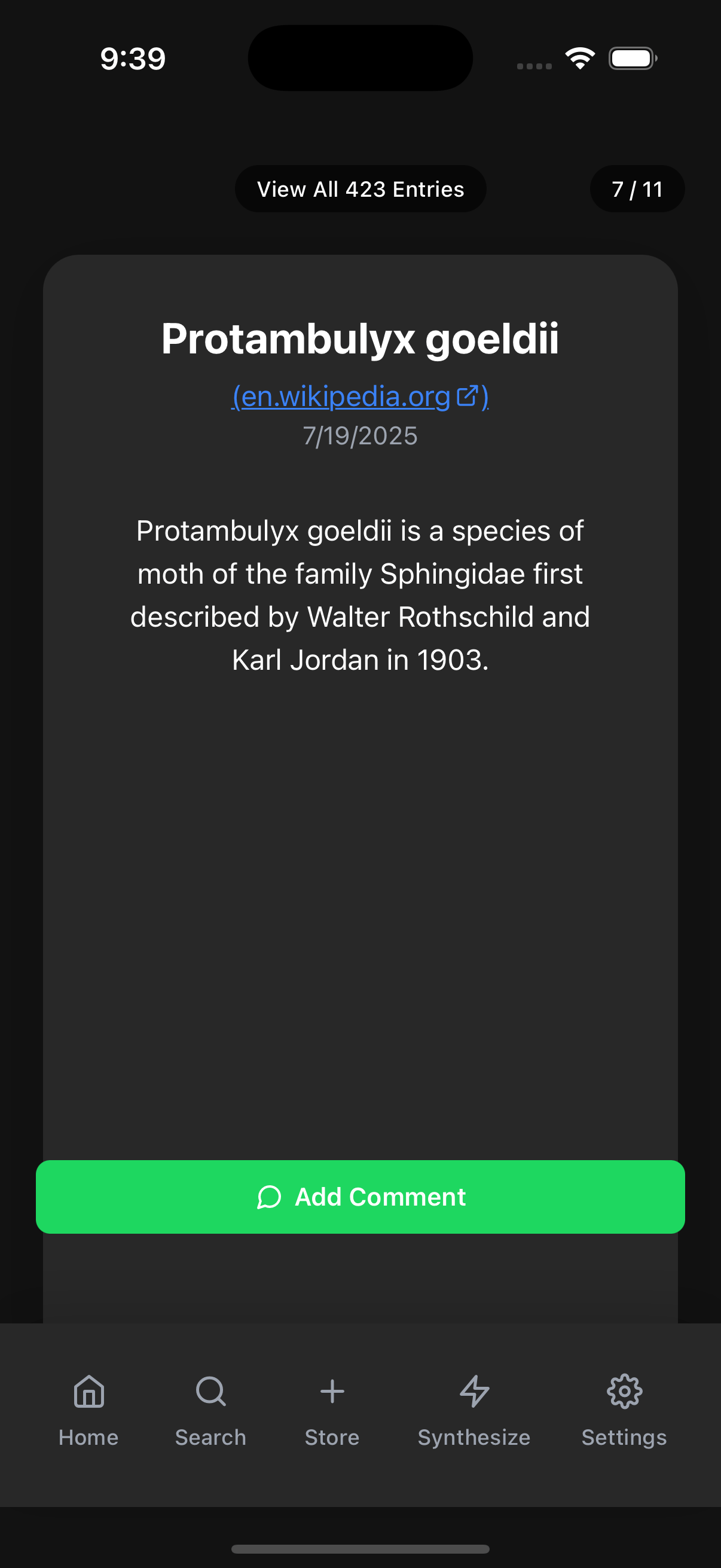

top right corner 7/11, scrolls like short form video content, but only with stuff you’ve saved. Win win!

4. Entry Page Relationships

Recently, my thinking of what YCB is is a simple ledger of indexes of relationships (ask me about it). Some of these relationships are explicit (i.e., they are forcibly tied together, sometimes violently so). Other of these relationships are implicit or coincidental, much like how you live next door to your neighbors even though you might never have met them before. You share something in common without even knowing each other.

Seeing both of these next to each other, next to the source data that it came from, causes a really interesting effect on the mind and how it thinks about the relationships of things.

source data

Information is never alone! Threads are comment chains, neighbors are surfaced from embeddings clusters

Store [Ideas]

A number of the engineers read prodigious amounts of science fiction. Dave Keating, for instance, read three or four novels of this sort a week. “For one,” he explained, “science fiction has a lot of optimism in it. I mean, we made it that far at least. Part of it, too, we can identify with the technology; and I like the imagination in those books.” Several of them, at idle moments, liked to conjure up stories of their own. Chuck Holland told me: “I do a lot of thinkin’ about what my mind must do. The way I think it’s gonna be is that the computer will grow up with the child. When you’re born, you’ll be given a computer. There’ll be this little thing”—he grabbed his shoulder to show where it would sit—“that goes around with you. You’ll teach it how to talk after you learn how.” He imagined a teenaged boy teaching his computer how to drive, telling it, “Okay, now you give it a try,” and correcting it when it made a mistake. “It’s gonna be an extension of me,” Holland said. But maybe, he went on, a time would come when the home would be “practically a simulator,” and the computer would run every aspect of a person’s life. “Then we get tired of it. We start growing plants or something. Maybe slowly we will turn around and go away from it. If computers take something away from us, we’ll take it back. Probably a lot of people will get screwed before that happens.”

MORSE NEVER SAW the birth of the inventions that would overshadow the telegraph. He agreed to unveil a statue of Benjamin Franklin in Printing House Square in New York, but exposure to the bitterly cold weather on the day of the ceremony weakened him considerably. As he lay on his sickbed a few weeks later, his doctor tapped his chest and said, ‘‘This is the way we doctors telegraph, Professor.’’ Morse smiled and replied, ‘‘Very good, very good.’’ They were his last words. He died in New York on April 2, 1872, at the age of eighty-one, and was buried in the Greenwood Cemetery. Shortly before his death, his estate had been valued at half a million dollars—a respectable sum, though less than the fortunes amassed by the entrepreneurs who built empires on the back of his invention.

Selecting the genuine takes work; then forgetting takes even more work. This is the curse of omniscience: the answer to any question may arrive at the fingertips—via Google or Wikipedia or IMDb or YouTube or Epicurious or the National DNA Database or any of their natural heirs and successors—and still we wonder what we know. We are all patrons of the Library of Babel now, and we are the librarians, too. We veer from elation to dismay and back. “When it was proclaimed that the Library contained all books,” Borges tells us, “the first impression was one of extravagant happiness. All men felt themselves to be the masters of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal or world problem whose eloquent solution did not exist in some hexagon. The universe was justified.” Then come the lamentations. What good are the precious books that cannot be found? What good is complete knowledge, in its immobile perfection? Borges worries: “The certitude that everything has been written negates us or turns us into phantoms.” To which, John Donne had replied long before, “He that desires to print a book, should much more desire, to be a book.” The library will endure; it is the universe. As for us, everything has not been written; we are not turning into phantoms. We walk the corridors, searching the shelves and rearranging them, looking for lines of meaning amid leagues of cacophony and incoherence, reading the history of the past and of the future, collecting our thoughts and collecting the thoughts of others, and every so often glimpsing mirrors, in which we may recognize creatures of the information.

Best,

Bram